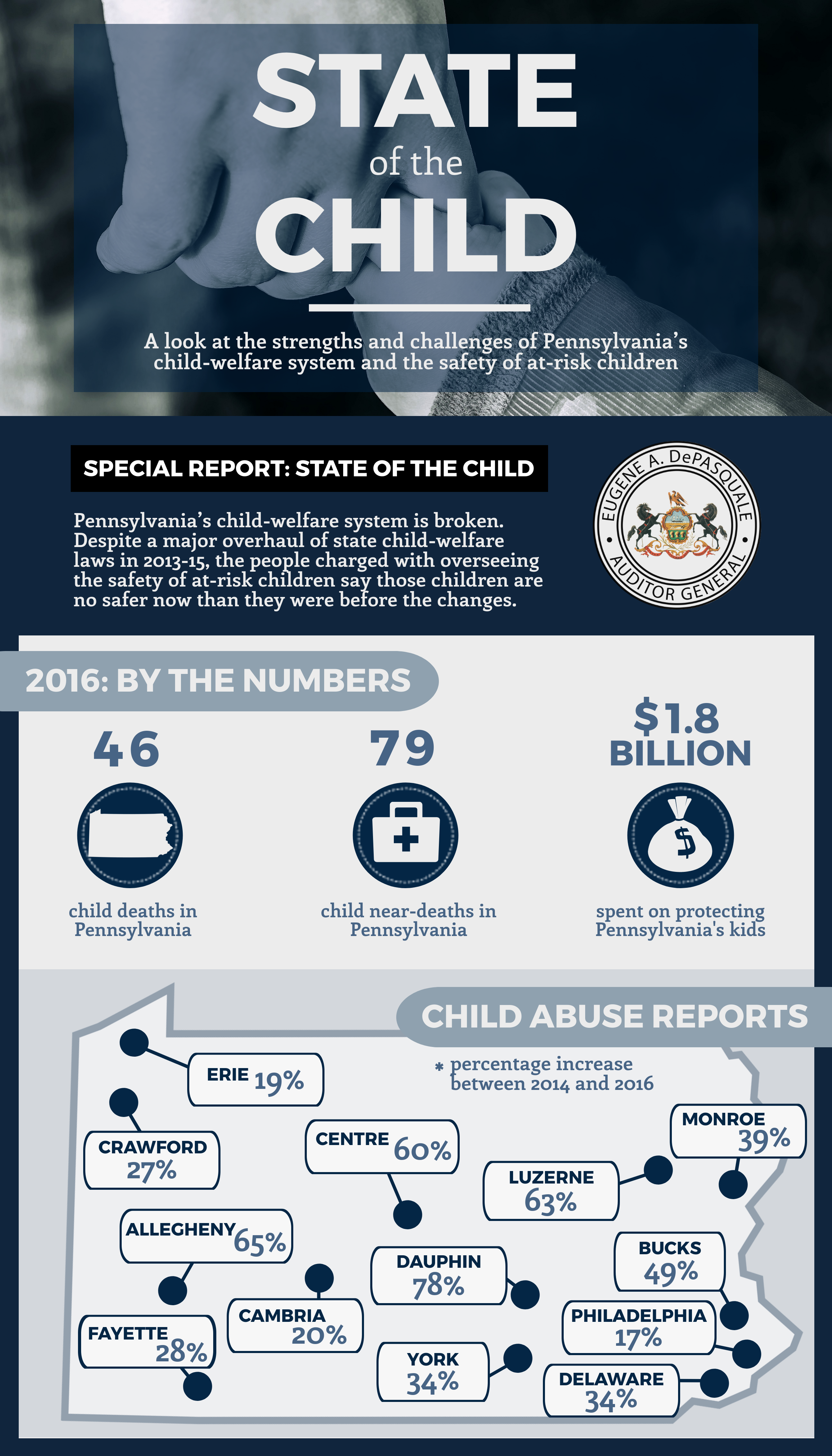

Auditor General DePasquale Says ‘State of the Child’ Special Report Shows Broken Child-Welfare System Broken Puts Children at Risk

Auditor General DePasquale Says ‘State of the Child’ Special Report Shows Broken Child-Welfare System Broken Puts Children at Risk

Dedicated professionals trying to protect kids, but overwhelming caseloads, opioids hinder efforts

HARRISBURG (Sept. 14, 2017) – The system is broken. And Pennsylvania’s at-risk children are not safe.

Auditor General Eugene DePasquale today said those facts are what a year-long review of Pennsylvania’s children and youth services (CYS) system showed him.

“What I found for my ‘State of the Child’ report is appalling,” DePasquale said. “I’m talking about wholesale system breakdowns that actually prevent CYS caseworkers from protecting our children from abuse and neglect.”

The 80-page “State of the Child” special report assesses the strengths and challenges of Pennsylvania’s child-welfare system. Specifically, it focuses on county CYS caseworkers, who are on the front lines of working with children and their families.

“Children are being horribly abused and neglected in Pennsylvania every day,” DePasquale said. “In recent months, we’ve heard of toddlers being kept in cages, newborns left home alone and starving school-age children locked in filthy rooms. There are heartbreaking stories every week.

“Yet, all told, Pennsylvania spent more than $1.8 billion in 2016 to protect children,” he continued. “When I audited ChildLine, the state’s child-abuse hotline, last year and found massive problems that required immediate action, I knew I needed to look further into how the entire child-welfare system was operating.”

The results of that review, DePasquale said, are staggering.

“We spent nearly $2 billion dollars in 2016, yet 46 children died and 79 nearly died from abuse that year,” he said. “What really disturbs me is that nearly half of the children who died were in families that were already known to CYS.”

The special report contains seven report observations and 17 recommendations for improvement. It highlights five interlaced challenges that severely impact caseworkers’ ability to do their jobs effectively:

- Difficulty finding enough qualified professionals, who then

- Receive inadequate training to handle the job’s

- Heavy caseloads and burdensome paperwork, plus

- Remarkably low pay, lead to

- Breath-taking turnover rates.

“We discovered, for example, that York County had 90 percent turnover in its caseworkers in a 24-month period,” DePasquale said. “Ninety percent. How do you have any continuity of care for these vulnerable kids and families? The answer is you don’t — and the kids suffer because of it.”

Two other report observations examine other current state-level reviews of the system and how two other states — Florida and Arizona — have dealt with similar challenges in their child-welfare systems.

Legislative changes, opioid impact

Pennsylvania’s child-welfare system has been struggling to retain workers and keep up with the demand of helping children and families for years, experts said for this report. But in 2015, in the wake of the Jerry Sandusky child-sex-abuse scandal, major legislative changes to the Child Protective Services Law (CPSL) took effect, including:

- An expanded definition of child abuse, and

- An expansion of those considered mandated reporters.

As more people became legally required to report suspicions of abuse or neglect, and the definition of what constitutes abuse broadened, county CYS agencies were inundated with cases to investigate. As a result, caseworkers who make the initial contact with families, known as Intake caseworkers, went from having generally manageable caseloads of about 12 to 20 to juggling sometimes more than 50 to 75 cases at a time.

“Intake caseworkers tend to be new college grads, fresh out of school and looking to make a difference in the world,” DePasquale said. “These are new professionals who often lack real-world experience with the types of volatile situations they encounter and are expected to manage.

“They are not trained in crisis management. They are not trained in motivational interviewing skills. They are not trained in self-defense. They are not trained to spot hazardous meth labs,” DePasquale continued. “They are just some of the people who put their own health and well-being at risk as they enter dangerous situations and make life-changing decisions for the most vulnerable among us.”

Changes to the CPSL also added volumes of paperwork required for each case, so that Intake caseworkers can spend up to three hours recording a 45-minute visit with a family. Add in the tight, strict deadlines for when caseworkers have to see at-risk children and for when the voluminous paperwork had to be filed with the state, and the pressure of the job began to burn out even veteran caseworkers.

When the job stress became too great, caseworkers began to leave in droves — placing more burden and work on the remaining stressed-out caseworkers, who then had to pick up those outstanding cases.

“Those ‘outstanding cases’ were children living in environments where they might be beaten, starved or neglected,” DePasquale said. “And nobody had the time to make sure those kids were kept safe.”

At the same time, the use of opioids in the state began to sky-rocket, creating a ripple effect on the CYS system. Caseworkers now deal with scores more people abusing heroin or prescription painkillers, industry experts said for this report.

“We know opioid addiction rips families apart,” DePasquale said. “When families are no longer functional, it’s the job of CYS to step in and provide support and assistance.

“However, CYS agencies have been drowning in paperwork and staff turnover, so their primary mission of protecting children has been lost in the frantic rush just to survive each day.

“Overregulation and a shortage of critical resources have resulted in kids being left in situations that led to their deaths. It’s that simple.”

Moving forward

DePasquale said it’s too late to focus on the mistakes of the past that led to today’s unstable system. Instead, he’s looking to the future, offering 17 recommendations for changes that will make a difference in remedying some of the deficiencies in the system.

“Child welfare in this state is administered through a piecemeal system that doesn’t receive adequate resources from state or county governments,” DePasquale said. “It’s not only a matter of providing adequate funding and resources but also a matter of using the resources the state and counties have efficiently and effectively.”

DePasquale’s major recommendation is for DHS to create an independent child protection ombudsman position so that one person within the department is tasked with advocating for Pennsylvania’s at-risk children.

Other recommendations include revamping requisite training, reducing paperwork and assessing whether using new technology could allow caseworkers to spend more time in the field with troubled families.

“As a society, our goal must be clear: No child should ever be mistreated, because one abused child is one too many,” DePasquale said.

‘Overwhelming response’

DePasquale and his team talked with nearly 130 people for this special report, including more than 50 CYS caseworkers, supervisors and administrators in 13 counties; as well as 38 families who had been or are currently involved in the CYS system.

“The overwhelming response we’ve had since we announced this special report is unprecedented,” DePasquale said. “It has obviously touched a nerve with the general public and with those directly involved with the system.”

The “State of the Child” special report is available online at: www.PaAuditor.gov.

# # #

Media contact: Susan Woods, 717-787-1381

EDITOR’S NOTE:

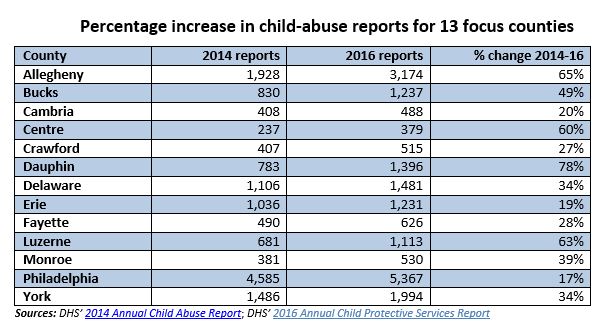

- For detailed data about your county’s child-abuse reports, see DHS’ 2016 Annual Child Protective Services Report.

- Attached is a table showing the percentage increase in child-abuse reports for each of the 13 focus counties from 2014-16.